Q&A: Anika Pyle on Remembrance, Poetry, & More in ‘Wild River’

☆ By FRANKIE TAMERON ☆

Photos By Jess Flynn

PREVIOUSLY KNOWN AS THE FRONTWOMAN FOR CHUMPED — in 2013, Anika Pyle toured with bands such as Pup, Roger Harvey, and Modern Baseball, entering the pop-punk world to spend a few years inspiring women to pick up a guitar.

Wild River is Anika Pyle’s debut solo LP and it is quite the departure from her pop-punk past. No longer singing about teenage retirement, Pyle has given us a record that is quite the listening paradox. Although there is a lot of noise on the tracks, the music coming through the headphones is quiet. Drawing inspiration from her childhood in Colorado, Pyle has captured moments of stillness within the woods and down by the river and turned them into music using only her voice and her guitar.

The record came to life after playing a show at the Philadelphia Free Library that asked her to mix poetry and song in her set; pulling together material just a few weeks after her father’s passing, Wild River was born as a way to remember everything that she was processing at the time. From the first track to the last, we are given a mix of poetry and song, each one diving deeper into Pyle’s grieving heart. The album’s title track opens with samples of her grandmother and Pyle’s poetry spoken over chords, and it is reminiscent of snowfall at 3 a.m.: soft and hauntingly beautiful.

Read below to get real with Pyle, as Luna sat down for a vulnerable conversation about finding herself as a solo artist, imposter syndrome, the importance of telling our own stories, and Wild River.

LUNA: During my Anika Pyle deep dive, I was streaming another interview and you said that writing has always been your retreat. As a writer, I definitely understand that. Why did you choose music and why do you keep doing it?

PYLE: Music is so chemically and somatically — our brains love to hear music. It doesn’t really matter what kind of music it is; it’s not like the brain really loves metal over classical. Our own brain is wired towards what we are drawn towards. I don’t know what the studies say about listening to music, but it is such a healing medium. Making music, though — I think I have the same experience. It’s like the thing that happens where I lose time — I lose track of time when I’m writing a song. I can be writing a song to process something and it’s already 8 o’clock and I haven’t eaten dinner or drank water, and I’ve entered this other universe. And I think that’s why I keep coming back to it. Music is a spiritually healing experience in itself.

LUNA: I love that. Lately, I find myself thinking that I should start making music. But, thinking about it is terrifying for some reason. Do you find that it’s more vulnerable to make music than poetry or prose, or any other creative work?

PYLE: I think it’s scarier to make music than it is to write poetry. I think part of that is because the music I make is more likely to be shared, so I have to get into this space where I’m still writing for the experience of writing and the experience of sharing. Whereas when I write poetry it’s more of a private process and I’m less in the rhythm of sharing that with people, so it feels a little bit more clandestine. Making stuff is scary.

LUNA: What was it like putting out music as a solo artist as compared to Chumped and Katie Ellen? How does it feel to be doing it on your own as opposed to just a few years back with these bands?

PYLE: It feels both very lonely and very empowering. I love the feeling of writing with a band and bringing a song to other people that you trust — they can help you take it to this next level. There’s this beautiful chemistry that comes with playing with a band, and doing it alone I have to challenge myself to make my own chemistry. It’s a different experience — it’s much more introverted, self-explorative, and less … fun. It’s a different kind of fun; it’s a new challenge. A lot of growing — a lot of uncomfortable growing.

LUNA: Are you enjoying the process?

PYLE: I am, yeah! I think I set myself up for alone time for a while, because of the reality of everything, but it’s a good place to be.

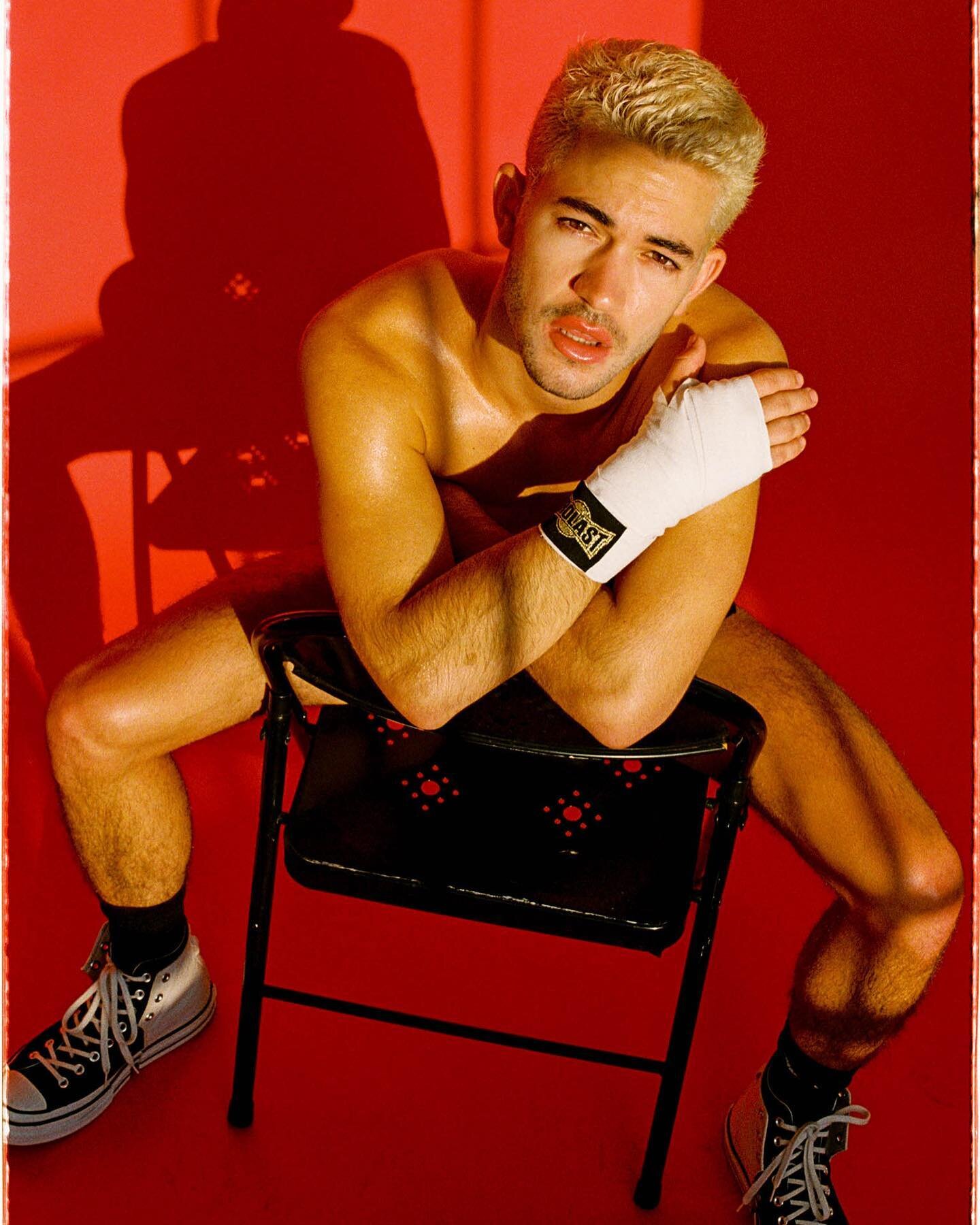

Photo By Autumn Spadaro

LUNA: What’s it like to be a female musician? You’re kind of in a male dominated industry — what’s it like now compared to your earlier career? Did you ever feel like you were competing to “run with the boys” or is that culture non-existent?

PYLE: I think that the landscape of music is so different now. I think — especially when I was in a pop punk band — I definitely felt more like I was fighting for a place. I definitely felt out of place in a lot of ways, since pop-punk is very much a boys club. When I stepped outside of that bubble — and a lot of things that have happened in the last five years with people appreciating the expansiveness of gender and thinking outside this idea of binary gender — I feel much more at home, currently. I feel able to appreciate and discover so many different identities within the community of music that I’m making currently.

LUNA: When I first heard the new album, I had a couple of intense reactions to it. I felt all of your grief, but I also felt a sense of “I wanted to do that” in regards to making a poetry record. Did you intend to write Wild River so deep and raw?

PYLE: I have a hard time not writing from a place that is deep and raw. I like those words because I see music as a way to tap into things that I can’t really articulate. It gives me a new medium [away] from poetry. Music and poetry aren’t completely synonymous but for some reason when you tap into this poetry persona, you have access to these things that you might not be able to articulate otherwise. So sometimes I plan to hit something when I write, like, “I’m trying to access this —how do I get there?” but a lot of the time I’m just sitting down at the guitar or the keys, and I really need to get something out and I don’t know how to do it. I end up just searching and allowing the feelings to come up as it goes.

But I want to speak to what you said before that because it reminds me of a couple of things I’ve been thinking about. Creative people experience this feeling of gratitude and jealousy all the time. This person does this art thing and suddenly I’m like, “Fuck, I can’t do that.” I experience this as a yoga teacher: I have moments of “Why would I teach yoga if Yoga With Adriene exists?” The thing is, I feel like we operate in this mode of creative scarcity — and I’ve been really trying to step out of that. I need to recognize my feelings and ask myself what that means. At the same time, though, we can take someone else’s experience and be like, “OK, we are different people coming at this from completely different angles.” As creatives, we are working within the same medium, but there’s room for everyone to make the things that they want to make — and a necessity for everybody to make the things that they need to make, because you never know how your story is going to resonate with someone. I feel like often — especially in commercial industries — we have a lot of, “They already did it, so I can’t.” I just hope that all of these creators can get away from this feeling of scarcity, because we need everybody’s stories.

LUNA: I think a lot of the feelings you’re talking about is a form of imposter syndrome, and just this innate fear of failure we have has human beings. What would you do if you couldn’t fail?

PYLE: Something that I really want to do — and will do — is write a book. I sort of did that with this record, because the record comes with a book that accompanies the music. But I really want to publish a book. It’s been a goal of mine for about five years, and I’ve never put any time towards it and I think that’s because I’m afraid. I have so much poetry, though, that I should start with a book of poems.

LUNA: Going back to Wild River, did you ever think that you got too deep or too vulnerable, and like you should reel it back in?

PYLE: I think there were only moments that I felt that it was too vulnerable because I didn’t want it to feel like I was commodifying my own grief process. And part of me felt like [it was] a necessity to say all the things that I needed to say but also, you know, be respectful of my relationship with my dad and my grandmother who are both no longer living. I think that they are both proud of the record and happy that it exists. But sometimes I think whenever you’re ever referencing a relationship with someone else, you want to go as deep as possible while still respecting the other party. It’s kind of just ethics of writing — especially when you can’t ask for permission to publish something if someone is deceased. I think that was the only consideration of “How deep do I want to go with this,” because it was going to be shared.

LUNA: Did you draw a lot of inspiration from Colorado for this album?

PYLE: The record is very nature-heavy. There’s a lot of imagery about nature, you know — the Wild River is like [how I] grew up fishing together with my dad and going to the reservoir and the Colorado River. As I was writing, there was a lot of reflecting on being a little kid and how much nature was a part of my life when I lived in Colorado, and how important it was to my dad at certain points of his life. There is a cyclical nature of life and death and how that is mimicked in the natural world so much more than in the urban world — Colorado played a big part in the record.

LUNA: How did you decide to put the poetry versus the songs on the record?

PYLE: All the poetry on the record was poetry; there are a few songs that started as poems — there’s one in particular that was a series of haiku set to music specifically for the record. All the other spoken word were really meant to stay that way. I wanted to merge song and poetry — my two loves — that was the most authentic representation of myself that I could get to.

LUNA: Are the tracks in any sequential order?

PYLE: It’s definitely very highly sequenced; this record makes no sense if you start on track four first. It’s not commercially palatable — it’s like reading a book. It was definitely the most thoughtfully sequenced record I’ve ever made.

LUNA: Regardless of how the tracks are listened to, the album is still very raw and real-sounding as a whole. It listens like a bit of a demo. Did you intend that?

PYLE: I’m very attached to lo-fi stuff. The way that we recorded the record [is that] I just played a classical guitar and sang at the same time. So we captured the tracks simultaneously, which put more noise on the tracks. It’s definitely a stylistic choice. I’m very much a bedroom pop person. It’s definitely not a clean sound, but I like it.

CONNECT WITH ANIKA PYLE

SPOTIFY

-

From Pavietra 🕊️ https://t.co/BXVgWlZud8

-

slowthai by Rosie Matheson 🤩 https://t.co/z7SDfFQ5iF

-

RT @i_D: Ian Kenneth Bird photographs young punks on Polaroid: https://t.co/MKT0tMUqO9 https://t.co/a0tTl12ML5

-

RT @AnOtherMagazine: #DreamHome – this isolated idyll in the mountains of Lanzarote 🌵 📸 via Nowness, photography by Clemence Blr 🔁 https://t.co/GUusdxD0cg